One Temple

From The Beautiful Necessity "IV The Bodily Temple" by Claude Bragdon, FAIA

Carlyle says: “There is but one temple in the world, and that is the body of man.” If the body is, as he declares a temple, it is not less true that a temple or any work of architectural art is a larger body which man has created for his own uses, just as the individual self is housed within its stronghold of flesh and bones. Architectural beauty like human beauty depends upon the proper subordination of parts to the whole, the harmonious interrelation between these parts, the expressiveness of each of its function or functions, and when these are many and diverse, their reconcilement one with another.

Grow by Allison L. Williams Hill

This being so, a study of the human figure with a view to analyzing the sources of its beauty cannot fail to be profitable. Pursued intelligently, such a study will stimulate the mind to a perception of those simple yet subtle laws according to which nature everywhere works, and it will educate the eye in the finest known school of proportion, training it to distinguish minute difference in the same way that the hearing of good music cultivates the ear.

Merge with Krishna by Allison L. Williams Hill

Natural Beauty of the One Temple

Those principles of natural beauty which formed the subject of the two preceding essays are all exemplified in the ideally perfect human figure. Though essentially a unit, there is a well marked division into right and left – “Hands to hands, and feet to feet, in one body grooms and brides.” There are two arms, two legs, two ears, two eyes, and two lids to each eye; the nose has two nostrils, the mouth has two lips. Moreover, the terms of such pairs are masculine and feminine with respect to each other, one being active and the other being passive. Owing to the great size and one-sided position of the liver, the right half of the body is heavier than the left; the right arm is usually longer and more muscular than the left; the right eye is slightly higher than its fellow. In speaking an eating the lower jaw and under lip are active and mobile in relation to the upper; in winking it is the upper eyelid which is the more active. That “inevitable duality” which is exhibited in the form of the body characterizes its motions also. In the act of walking for example, a forward movement is attained by means of a forward and a backward movement of the thighs on the axis of the hips; this leg movement becomes twofold again below the knee, and the feet move up and down independently on the axis of the ankle. A similar progression is followed in raising the arm and hand: motion is communicated first to the larger parts, through them to the smaller and thence the extremities, becoming more rapid and complex as it progresses, so that all free and natural movements of the limbs describe invisible lines of beauty in the air. Coexistent with this pervasive duality there is a threefold division of the figure into trunk, head and limbs: a superior trinity of head and arms, and an inferior trinity of trunk and legs. The limbs are divided threefold into upper-arm, forearm, and hand; thigh, leg and foot. The hand flowers out into fingers and the foot into toes, each with a threefold articulation; and in this way is affected that transition from unity to multiplicity, from simplicity to complexity, which appears to be so universal throughout nature, and of which a tree is the perfect symbol.

Feminine Energy by Allison L. Williams Hill

The body is rich in veiled repetitions, echoes, consonances. The head and arms are in a sense a refinement upon the trunk and legs, there being a clearly traceable correspondence between their various parts. The hand is the body in little – “Your soft hand is a woman of itself” – the palm, the trunk; the four fingers, the four limbs; and the thumb, the head; each finger is a little arm each finger tip a little palm. The lips are lids of the mouth; the lids are the lips of the eyes – and so on. The law of Rhythmic Diminution is illustrated in the tapering of the entire body and of the limbs, in the graduated sizes and lengths of the palm and the toes, and in successively decreasing length of the palm and the joints of the fingers, so that in closing the hand the fingers describe the natural spirals. Finally, the limbs radiate as it were from the trunk, the fingers from a point in the wrist, the toes from a point in the ankle. The ribs radiate from a the spinal column like the veins in a leaf from its midrib.

Architecture and the One Temple

The relation of these laws of beauty to the art of architecture has been shown already. They are reiterated here only to show that man is indeed the microcosm - a little world fashioned from the same elements and in accordance with the same Beautiful Necessity as is the greater world in which he dwells. When he builds a house or a temple he builds it not literally in his own image, but according to the laws of his own being and there are correspondences not altogether fanciful between the animate body of flesh and the inanimate body of stone. Do we not all of us, consciously or unconsciously, recognize the fact of character and physiognomy in buildings? Are they not, to our imagination, masculine or feminine, winning or forbidding – human, in point of fact – to a greater degree than anything else of man’s creating? They are this certainly to a true lover and student of architecture. Seen from a distance the great French cathedrals appear like crouching monsters, half beast, half human: the two towers stand like a man and a woman, mysterious and gigantic, looking out over city and plain. The campaniles of Italy rise above the churches and houses like the sentinels of a sleeping camp- nor is their strangely human aspect wholly imaginary: these giants of mountain and campagna have eyes and brazen tongues; rising four square, story above story , with a belfry or lookout, like a head, atop, their likeness to a man is not infrequently enhanced by a certain identity or proportion - of ratio, that is, of height to width; Giotto’s beautiful tower is an example.

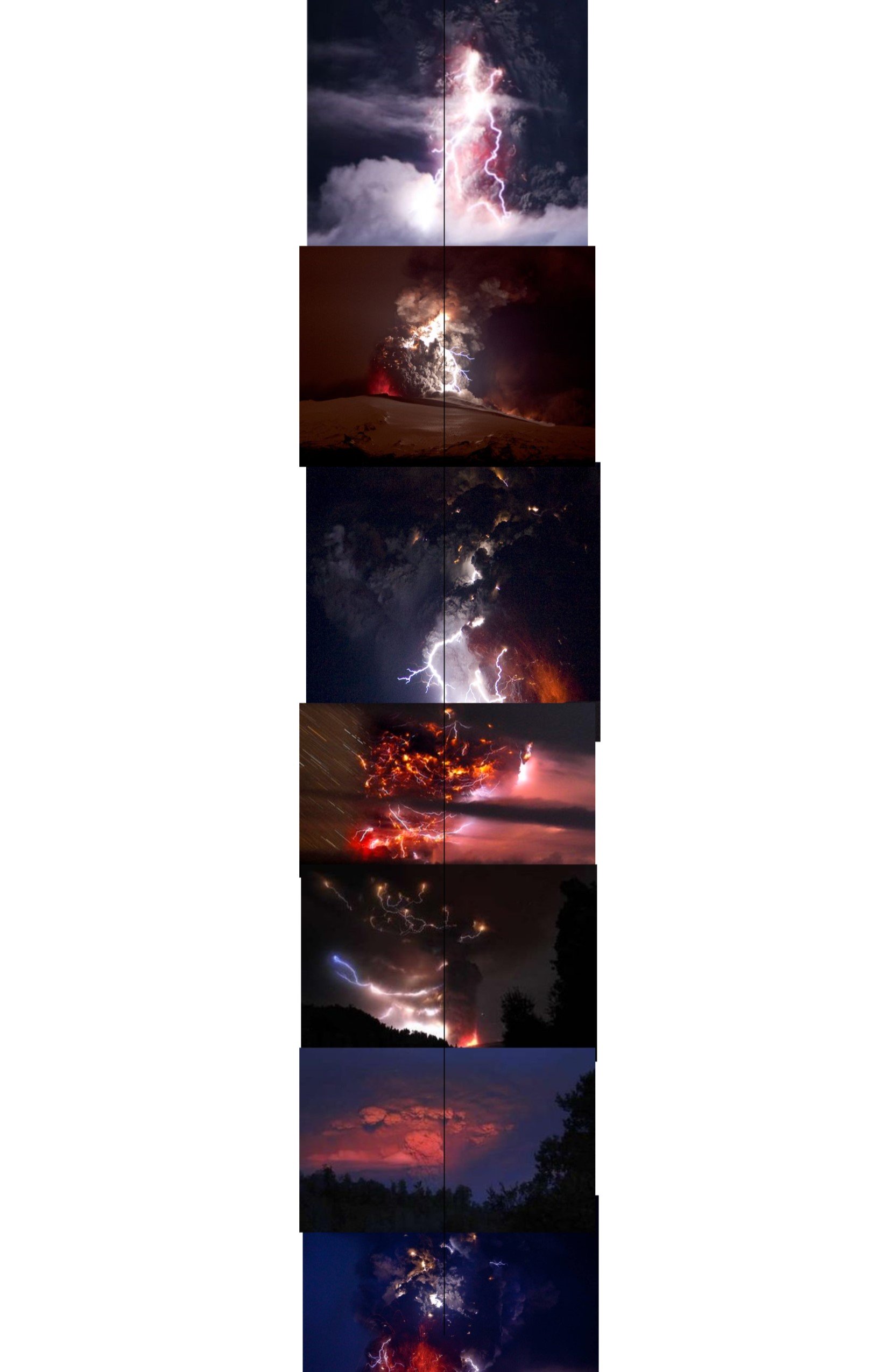

Temple Caryatids of the Erechthelon in Greece. It was recently discovered that these statues were colorfully painted.

The caryatid is a supporting member in the form of a woman; in the Ionic column we discern her stiffened, like Lot’s wife, into a pillar with nothing to show her feminine but the spirals of her beautiful hair. The columns which uphold the pediment of the Parthenon are unmistakably masculine: the ratio of their breadth to their height is the ratio of the breadth to the height of a man.

Japan 3 by Allison L. Williams Hill

Sacred Temple

At certain periods of the world’s history, periods of mystical enlightenment, men have been wont to use the human figure, the soul’s temple, as a sort of archetype for sacred edifices. The colossi, with calm inscrutable faces, which flank the entrance to Egyptian temples; the great bronze Buddha of Japan, with its dreaming eyes; the little known colossal figures of India and China – all these belong scarcely less to the domain of architecture than of sculpture. The relation above referred to however is a matter more subtle and occult than mere obvious imitation on a large scale, being based upon some correspondence of parts, or similarity of proportions, or both. The correspondence between the innermost sanctuary or shrine of a temple and the heart of a man, and between the gates of that temple and the organs of sense is sufficiently obvious, and a relation once established, the idea is susceptible of almost infinite development. That the ancients proportioned their temples from the human figure is no new idea, nor is it at all surprising. The sculpture of the Egyptians and the Greeks reveals the fact that they studied the body abstractly, in its exterior presentment. It is clear that the rules of proportions must have been established for sculpture, and it is not unreasonable to suppose that they became canonical in architecture also. Vitruvius and Alberto both lay stress on the fact that all sacred buildings should be founded on the proportions of the human body.1

Notre Dame facade

In France, during the Middle Ages, a Gothic cathedral became, at the hands of the secret Masonic guilds, a glorified symbol of the body of Christ. To practical-minded student of architectural history, familiar with the slow and halting evolution of a Gothic cathedral from a Roman basilica, such an idea may seem to be only the maunderings of a mystical imagination, a theory evolved form the inner consciousness, entitled to no more consideration that the familiar fallacy that vaulted nave of a Gothic church was an attempt to imitate the green aisles of a forest. It should be remembered however that the habits of the thought of that time was mystical, as that of o own age of utilitarian and scientific; and the chosen language of mysticism is always an elaborate and involved symbolism. What could be more natural than a building devoted to the worship of a crucified Savior should be made a symbol, not of the cross only, but of the body crucified?

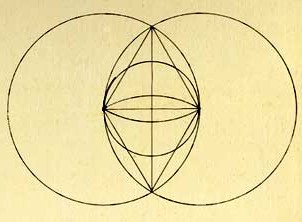

Vesica Pisces Crop Circle

Vesica Pisces 2-Dimension Geometric Drawing

The vesica piscis (a figure formed by the developing arcs of two equilateral triangles having a common side) which in so many cases seems to have determined the main proportion of a cathedral plan – the interior length and width across the transepts – appears as an aureole around the figure of Christ in early representations, a fact which certainly points to a relation between the two. The Rosicrucians, by Hargreave Jennings, contains an interesting diagram which well illustrates this conception of the symbolism of a cathedral. The apse is seen to correspond to the head of Christ, the north transept to his right hand, the south transept to the left hand, the nave to the body and the north and south towers to the right and left feet respectively.

Unidentified Cathedral Ruin

The cathedral builders excelled all others in the artfulness with which they established and maintained relation between their architecture and the stature of a man. This is perhaps one reason why the French and English cathedrals, even those of moderate dimensions are more truly impressive than even the largest of the great Renaissance structures, such as St. Peter’s in Rome. A gigantic order furnishes no true measure for the eye: its vastness is revealed only by the accident of some human presence which forms a basis of comparison. That architecture is not necessarily the most awe-inspiring which gives the impression of having been built by giants for the abode of pygmies; like the other arts, architecture is highest when it is most human. The mediaeval builders, true to this dictum, employed stones of a site proportionate to the strength of a man working without unusual mechanical aids; the great piers and columns, built up of many such stones, were commonly subdivided into clusters, and the circumference of each shaft of such a cluster approximated the girth of a man; by this device the moulding of the base and the foliation of the caps were easily kept in scale. Wherever a balustrade occurred it was proportioned not with relation to the height of the wall or the column below, as in classic architecture, but with relation to man’s stature.

Thought by Allison L. Williams Hill

It may be stated as general rule that every work of architecture, of whatever style, should have somewhere about it something fixed and enduring to relate it to the human figure, if it be only a flight of steps in which each one is the measure of a stride. In the Farnese, the Riccardi, the Strozzi, and many another Italian palace, the stone seat about the base gives scale to the building because the beholder knows instinctively that the height of such a seat must have some relation to the length of a man’s leg. In the Pitti palace the balustrade which crowns each story answers a similar purpose: it stands in no intimate relation to the gigantic arches below, but is of a height convenient for lounging elbows. The door to Giotto’s campanile reveals the true size of the tower as nothing else could, because it is so evidently related to the human figure and not to the great windows higher up on the shaft.

The geometrical plane figures which play the most important part in architectural proportion are the square, the circle and the triangle; and the human figure is intimately related to these elementary forms. If a man stand with heels together, and arms outstretched horizontally in opposite directions, he will be inscribed as it were, within a square; and his arms will mark with fair accuracy, the base of an inverted equilateral triangle, the apex of which will touch the ground at his feet. If the arms be extended upward at an angle, and the legs correspondingly separated, the extremities will touch the circumferences of a circle having its center in the navel.

Medium Pillars detail by Allison L. Williams Hill

The figure has been variously analyzed with a view to establishing numerical ratios between its parts (Illustrations 47, 48, 49). Some of these are so simple and easily remembered that they have obtained a certain popular currency; such as that the length of the hand equals the length of the face;

that the span of the horizontally extended arms equals the height; and the well known rule that twice around the wrist is once around the neck, and twice around the neck is once around the waist. The Roman architect Vitruvius, writing in the age of Augustus Caesar, formulated the important proportions of the statues of classical antiquity, and except that he makes the head smaller than normal (as it should be in heroic statuary), the ratios which he gives are those to which the ideally perfect male figure should conform. Among the ancients the foot was probably the standard of all large measurements, being a more determinate length than that of the head or face, and the height was six lengths of the foot. If the head was taken as a unit, the ratio becomes 1:8, and if the face – 1:10.

Doctor Rimmer, in his Art of Anatomy, divides the figure into four parts, three of which are equal, and correspond to the lengths of the leg, the thigh and the trunk; while the fourth part, which is two-thirds of one of these thirds, extends from the sternum to the crown of the head. One excellence of such a division aside from its simplicity, consists in the fact that it may be applied to the face as well. The lowest of the three major divisions extends from the top of the chin to the base of the nose, the next coincides with the height of the nose (its top being level with the eyebrows), and the last with the height of the forehead, while the remaining two-thirds of one of these thirds represents the horizontal projection from the beginning of the hair on the forehead to the crown of the head. The middle of the three larger division locates the ears, which are the same height as the nose.

Such analyses of the figure, however, conducted reveal an all-pervasive harmony of parts, between which definite numerical relations are traceable, and an apprehension of these should assist the architectural designer to arrive at beauty of proportion by methods of his own, not perhaps in the shape of rigid formulae, but present in the consciousness as a restraining influence,

acting and reacting upon the mind with a conscious intention toward rhythm and harmony. By means of such exercises, he will approach nearer to an understanding of that great mystery music, the beauty and significance of numbers, of which mystery music, architecture, and the human figure are equal representations - considered, that is, from the standpoint of the occultist.

Links

The above meditation mandala will be available soon.